Analysis

December 05, 2017

The notion that the note ban is an economic failure but a political success is a deeply flawed one

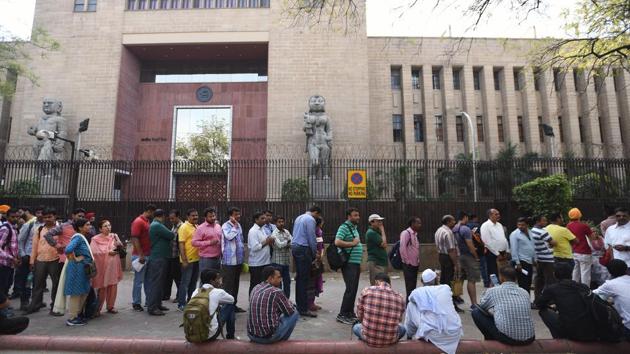

People queue up outside the RBI in New Delhi to submit their demonetised bank notes on last day of currency exchange in New Delhi, March 31. In India’s notorious first-past-the-post system, winning an election does not necessarily reflect increased popular support.

(Ravi Choudhary/HT PHOTO)

On December 30, 2014, there was a sudden announcement to ‘withdraw’ India’s ‘high-value’ cricketer, MS Dhoni, from circulation immediately. It shocked all Indian cricket fans. Dhoni was India’s captain and the most experienced player in the team. The ‘regulator’, Board of Control for Cricket in India (BCCI), was caught unawares and left to deal with the ramifications of this decision. There was uncertainty and trepidation for the future of Indian cricket. Only, Dhoni decided to ‘demonetise’ himself; this was not coercion. In the two years since the ‘Dhoni demonetisation’, India has won 20 of the 29 Test matches it has played, one of its most successful runs in its cricketing history. Dhoni ‘withdrew himself from circulation’ suddenly and India won most of the Test matches played immediately after. Does this mean that the sudden ‘demonetisation’ of Dhoni was a cricketing success? If this sounds bizarre, then so is the narrative that India’s sudden demonetisation of high-value currency was a political success.

This notion that demonetisation is an economic failure but a political success is a deeply flawed one. The popular wisdom is that because Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) won several state elections immediately after demonetisation, it is a political success. In India’s notorious first-past-the-post system, winning an election does not necessarily reflect increased popular support. If demonetisation was indeed a very popular move and earned plaudits among voters as claimed, then this should have reflected in the vote shares for the BJP in elections held immediately after demonetisation. In other words, more people should have supported the BJP after demonetisation than before. Is this true?

There were 578 assembly constituencies across 18 states where voters had a chance to exercise their support for the BJP after demonetisation on November 8, 2016. These include state elections and by-elections to both state assemblies and the Lok Sabha. These exact same 578 constituencies also had a BJP candidate in the 2014 Lok Sabha elections. Nearly 100 million Indians voted in these 578 constituencies in elections held after demonetisation. Forty-three per cent of them voted for the BJP in the 2014 elections. After demonetisation, 41% voted for the BJP. In other words, when exactly the same set of voters was given a chance to choose the BJP, fewer voters chose the BJP after demonetisation than before. To be sure, the difference is insignificant and cannot be attributed to demonetisation alone. But clearly this does not support the narrative that demonetisation was a hugely popular move among voters and spurred them to support the BJP in larger numbers. Even in terms of seats won, the BJP won 452 of these 578 constituencies before demonetisation; after, it won 408. If fewer voters chose the BJP after demonetisation than before, how can it be deemed as a political success? At best, one could argue that demonetisation did no harm to the BJP and did not pull down its support significantly. But surely it is incorrect to argue that it propelled the BJP to electoral victory.

The argument that demonetisation is a political success for the BJP is not very different from the argument that Dhoni’s sudden retirement was a cricketing success. This argument presupposes that the BJP would not have won these elections otherwise and demonetisation was instrumental in their victory. Any counterfactual proposition is difficult to prove, but if the scale and quality of the BJP victory in the 2014 elections is any indicator, then it is clear that it did not need a risky experiment such as demonetisation for it to win the elections that it did. It is evident that demonetisation was not a big negative to pull down the BJP’s support base but that is not the same as saying that it helped the BJP win elections and hence it is a political success.

Too often, pundits come up with big narratives to explain electoral outcomes based on a simplistic win-loss headline. This runs the risk of drawing the wrong conclusions and leading to false policy choices. Surely, the lesson from demonetisation for political parties cannot be that risky, audacious and ill-thought economic policies are good political strategies. To call demonetisation a political success is inaccurate.

Praveen Chakravarty is a political economist and senior fellow, IDFC Institute

(With inputs from Ishita Trivedi)

The views expressed are personal