Indulge in a thought experiment: It is June 2014. India has just elected a single party with a clear majority in Parliament in three decades. The Prime Minister designate has a strong reputation for economic development. Crude oil prices have halved from the previous year.

Exactly, the three most important requirements for an economic miracle in India — a full majority for the ruling party without being held to ransom by coalition partners, a focus on economic development by the Prime Minister and low oil prices for a large, oil dependent, fast growing economy such as India. If we had to guess what this miraculous alignment of stars would portend for the Indian economy, most of us would have rubbed our hands in glee and predicted a robust, double digit economic growth for five full years. In other words, we would have predicted the size of India’s economy to be $2.2 trillion in FY 2018 (at 10 per cent growth).

The Economic Survey 2017-18 tells us that India’s economy will most likely be $2 trillion. A lost potential output of $200 billion. This, at a time when there have been no global crises and oil prices have continued to fall (until just recently). The Economic Survey of 2017-18 leaves the reader with exactly this sympathetic sense of ‘what could have been’.

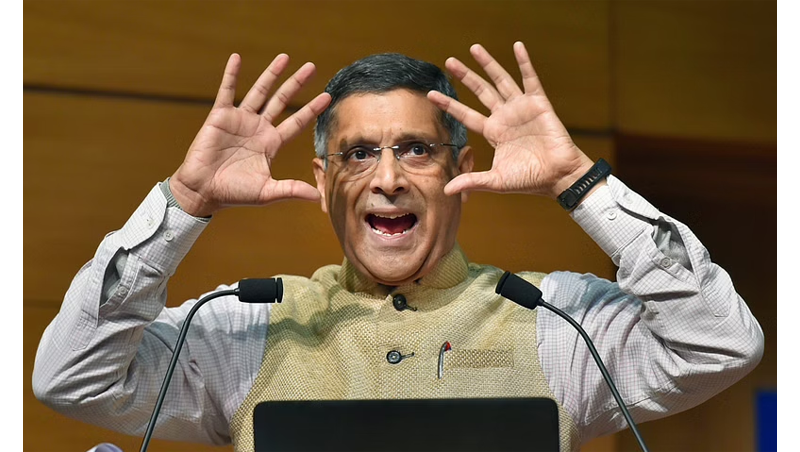

The 2018 Economic Survey by the Chief Economic Adviser, Arvind Subramanian and his team is yet another fantastic effort. Subramanian had raised the bar considerably higher with the surveys of the previous two years that one thought it would be very hard to emulate them. But he has done that yet again this year. The survey deftly traverses a wide spectrum of issues and ideas from the macro-economy to political economy to agriculture economy to social issues of women’s empowerment to climate change. It is rich with data, rigorous in analysis, punchy with ideas and emphatic in its recommendations.

India’s economy will grow at 6.5 per cent in FY 2018, lower than the lower end of the previous year survey’s prediction of 6.75 per cent — 7.5 per cent. In the backdrop of this disappointment, the survey is at pains to highlight how India’s economy may have bottomed out and there are ‘green shoots’ across all sectors from agriculture to exports.

But the CEA pulls no punches in the chapter on investment and savings slowdown arguing that ‘no other country seems to have gone through such a large investment boom and bust as India’. This is quite telling. The survey argues that India’s investment slowdown is unprecedented, has endured for too long, is far too detrimental to India’s growth and more ominously, is not yet showing signs of reversal.

The survey is categorical in its assertion that ‘mobilising household savings through attempts to unearth black money’ is not nearly as important as the need to revive investment, which has fallen from a peak of 36 per cent of GDP in 2007 to 26 per cent in 2016. Paraphrasing the CEA, he seems to say “let us not indulge in moralistic battles over black and white money as much as we should focus on getting investment back to 35-36 per cent of GDP”. Cannot disagree with that.

The real sobering part of the Economic Survey is its finding that Indian industry is still not showing signs of rapid revival. Growth in Index of Industrial Production (IIP) in manufacturing has fallen to 3.1 per cent from 4.4 per cent in FY17. Growth in production of eight core sectors such as steel, fertiliser, cement, electricity etc has slowed to 3.9 per cent from 4.8 per cent. Capacity utilisation is still flat at 71 per cent, the same level as in Q1 2017.

All these do not augur well for the quality of recovery of the Indian economy in the near term. And for all that talk about corporate India resorting to other sources for capital away from NPA infested banks, the overall growth in flow of credit to the industry is still negative. That is, India Inc is not borrowing enough which will hinder its ability to invest, expand and hire. While the survey gloats over some successes in sector specific policies such as in steel and textiles, it is always dangerous for the state to pick winners in an economy.

The only positive aspect in infrastructure seems to be in the roads sector that has seen a sharp growth both through new construction of national highways as well as conversion of state highways into national highways.

The Economic Survey highlights how the expected benefits of formalisation of India’s economy are being achieved through the introduction of GST. There are nearly 10 million businesses registered in GST and roughly 31 per cent of non-agriculture workers are in formal jobs. The survey also confirms some of my own earlier research findings of the large skew among states where just five of the 29 states of India account for half of all economic activity. The survey confirms that Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu, Gujarat, Karnataka and Uttar Pradesh account for half of all GST revenues and puts to rest the earlier apprehension that large states may be net revenue losers in a GST regime.

The other data point that caught my attention is the highlight that nearly 90 per cent of all organised sector ‘formal’ employees earn less than Rs 15,000 a month. To put that in context, a monthly wage for an unskilled, unorganised sector NREGA worker is Rs 6,000 a month. Behind these celebrations of formalisation of India’s economy lies the harsh reality of India’s poverty.

There has been much talk about India’s low tax to GDP ratio. The Economic Survey has a fascinating political economy insight to this. Using tax data at the municipal and local government level, the survey points out that local governments despite having taxation powers collect less than a tenth of potential tax revenues. In other words, municipal bodies are not levying and collecting enough taxes at the local level for their development.

The survey takes inspiration from Rabindranath Tagore to ask why is this the case and posits that perhaps the closer elected representatives are to the people, the more difficult it is to tax them, which runs entirely counter to the idea of taxation with representation form of electoral democracy.

Since, the first level of interface for most citizens is with their local governments, the hypothesis of the Economic Survey is that local governments find it hardest to collect taxes from their voters. India’s ability to raise tax resources at the level of local government is super critical to its longer term development as state capacity needs to grow commensurate with rapid urbanisation.

The Economic Survey 2018 serves a warning about “feminisation of agriculture and poverty”. It shows how there are 2 million ‘missing’ girls every year due to selective sex abortion, female infanticide or disease prevention. It argues that ‘son preference’ is still very high and rampant despite an equally rapid increase in male migration to urban towns, leaving women to tend to farms in rural areas. It is truly laudable that Subramanian picks such important social issues to discuss in detail in the Economic Survey as he has done over the past few years. While one may argue that there is no immediate policy intervention, it serves a tremendously useful purpose to shine light on such issues amid discussions of per capita GDP.

Overall, the Economic Survey 2018 is rich in detail and temperate in prognosis. The three stars of a ruling party’s Parliament majority, development agenda and low oil prices may never align again in our lifetime and we may come to rue these missed years. That is the biggest takeaway from Economic Survey 2018.

(Praveen Chakravarty is Senior Fellow, IDFC Institute)