There is no evidence to suggest that parliamentary behaviour is a consideration for voters — something that is obvious to most elected politicians.

Praveen Chakravarty

August 07, 2015

Ever since the monsoon session of Parliament began on July 21, there have been puns galore. “Washout amidst storms”, “Raining protests”, “Much thunder”, “Well overflowing”, “All down the drain” are some of the headlines (traditional and social media) that have appeared on the repeated adjournments and stalling of Parliament in the current session. NDTV claimed that a washout of the monsoon session would waste Rs 35 crore of taxpayer money. Times Now has claimed the figure is Rs 260 crore.

[related-post]

“No discussions without resignations” is the Congress’s mantra. Its member of Parliament, Shashi Tharoor, doesn’t agree with this strategy, and warned that it could incur the wrath of the voters. But, instead, it was he who earned the ire of Congress president Sonia Gandhi. Prime Minister Narendra Modi has cautioned that the world is watching India’s ugly stalemate in Parliament and that it does not bode well for the country’s image. To boot, some urbane politicians are trying to come up with smart 140-character prescriptions, such as “no subsidised lunch for MPs”, “no salary for non-working MPs”, etc. Amid this furore over a stalled House and reminders about India’s global reputation being tarnished as well as veiled threats on increasing the price of biryani for MPs, it is pertinent to ask if parliamentary performance and conduct matter electorally for an MP. In other words, do Indian voters reward or punish their elected representatives for good or bad parliamentary performance?

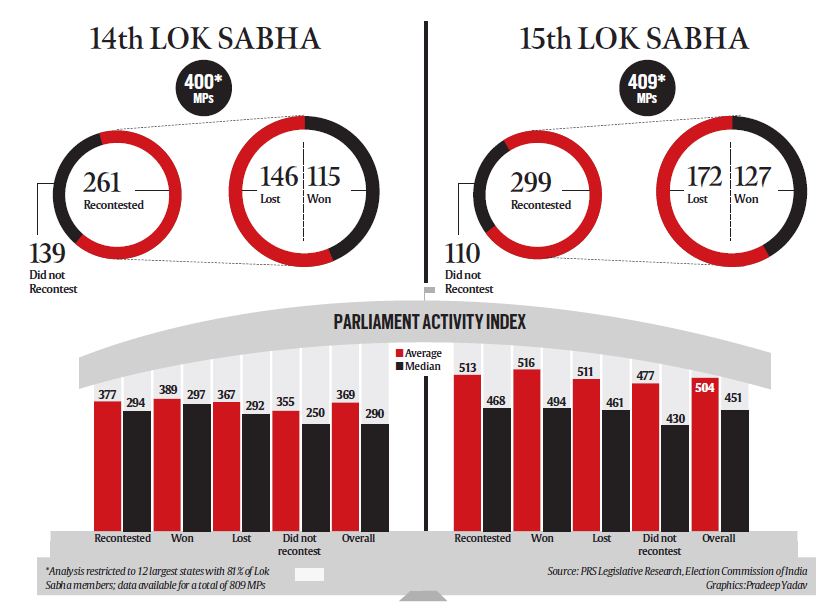

PRS Legislative Research, a 10-year-old Delhi-based non-profit, has meticulously compiled and made easily available data on MPs’ performance in Parliament in terms of attendance, participation in debates and questions asked. Using data from PRS for the 14th (2004-09) and the 15th (2009-14) Lok Sabhas, we analysed MPs’ parliamentary performance vis-à-vis their re-election campaigns across two general elections (2009 and 2014). We computed a simple cumulative “parliamentary activity index”, giving twice the weight to attendance as to participation in debates, which is often a party diktat, or asking questions. We restricted our analysis to the 12 largest states that account for 440 (81 per cent) of Lok Sabha members. We were able to get parliamentary activity data for a total of 809 MPs — 400 in the 14th Lok Sabha and 409 in the 15th Lok Sabha. Of these 809 MPs, 567 (70 per cent) faced re-election as a sitting MP in the 2009 or the 2014 election, or in both.

Did a good parliamentary track record attract more voters or ensure a higher vote-share for these MPs or vice versa?

According to this analysis, there is absolutely no relationship between an MP’s performance in Parliament and her popularity with voters. That is, when presented with the choice of rewarding or punishing an MP for her parliamentary performance, more than 500 million voters across two elections did not seem to care. A scatter plot examining the relationship between parliamentary record and swing in vote-share reveals no significant relationship. Interestingly, the only marginal impact we found was that MPs who did not recontest had a lower parliamentary activity index than those who did stand for election again. While it would be premature to conclude just on this basis that political parties hand out electoral tickets to candidates based on their performance in Parliament, there does seem to be a relationship between poor performance in the House and not recontesting elections. But when a sitting MP recontests, her parliamentary performance seems to matter very little for the eventual outcome or even just for her vote-share.

The table summarises both the average and median “Parliament activity index” for MPs who recontested and for those who did not, as well as the overall index scores for all MPs. MPs who won re-election did not have a significantly better parliamentary track record than the average MP, while those who lost did not have lower-than-average activity levels. This is true for both the 14th and 15th Lok Sabhas and the subsequent elections in 2009 and 2014. Thus, contrary to Tharoor’s warnings to his party, there is no evidence to claim parliamentary behaviour is a consideration for voters — something that is, perhaps, obvious to most elected politicians.

This is not an attempt to intellectualise the licence to stall Parliament. This is merely to clarify the incentives faced by politicians. If every MP is cognisant of the fact that absence in Parliament is not going to hinder her electoral chances and if “electability” is the primary criterion of handing tickets to candidates by political parties, what is the real penalty for an MP not discharging her duties in Parliament? An increase in prices in the Parliament canteen or taking away some of the MPs’ perks may save a few crores, but they are certainly not going to get our MPs racing to the House. Parliamentary performance must become an election issue and a primary re-election issue in every constituency. In India’s notoriously multi-cornered elections, where the margin between a win and a loss is very often a few thousand votes, the potential to swing votes marginally based on parliamentary performance could serve as a powerful incentive for MPs to engage and be productive in Parliament. The media has a pivotal role to play in educating voters about good and bad performers in the House. Apart from the attempts to elicit anger among voters with figures on the loss of taxpayer money, making people aware of their MPs’ parliamentary performance is a responsibility of our fourth estate.

The writer is visiting fellow in political economy at IDFC Institute and a donor to PRS Legislative Research.

With help from Swapnil Bhandari

https://indianexpress.com/article/opinion/columns/no-one-loves-parliament/