The robustness of the US federal set-up

Analysis

Praveen Chakravarty

November 09, 2020

The US may want to import Indian election systems, but India needs to import genuine decentralisation from US

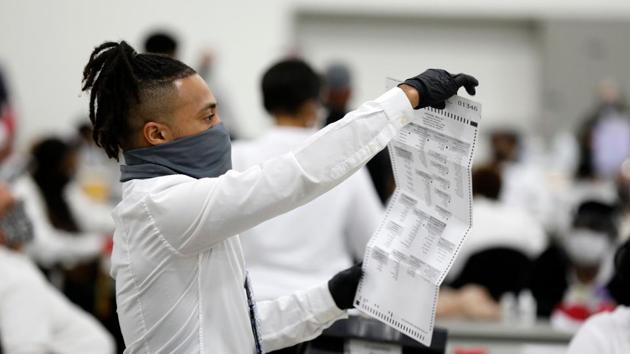

Detroit election workers work on counting absentee ballots for the 2020 general election, Michigan, November 4, 2020(AFP)

Detroit election workers work on counting absentee ballots for the 2020 general election, Michigan, November 4, 2020(AFP)

Joe Biden is the 46th President of the United States of America (US) after an arduous and messy presidential election. The American election has spewed many suppositions such as the “victory of Trumpism” or the “lingering death of liberalism”, for pundits to debate intensely over the coming weeks.

But one supposition seems beyond debate — India, the world’s largest democracy, runs elections better than the US, the world’s oldest democracy.

Indian national elections appear much more efficient than the American national elections. In India, votes are counted fast and results are announced by the end of counting day. Disputes over counting are few and rare. Never does an incumbent head refuse to vacate office after an electoral loss, at least not yet.

In contrast, the world has witnessed the chaos and disarray in the counting process of the US presidential election. It thus seems tempting for Indian commentators to offer some lessons to “big brother” and to export India’s more efficient election process to the US. But the seeming mess in the US’s electoral process is intentional and a small price to pay for a much larger good — federalism.

To elect their president in the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic, an American voter in the state of Pennsylvania could vote by mail but a voter in the state of Texas needed an excuse beyond Covid-19 to vote by mail. A voter in the state of New York made a choice between Donald Trump or Joe Biden, but a voter in neighbouring Maine ranked both the candidates in their order of preference. When the voting process to elect the president is uniquely different across each of the 50 states of the US, then inexorably, the counting process will be complex too.

Electing a president is arguably the most significant event for American democracy. Yet, there is no one set of national rules for electing the president. Each state has the powers to frame its own rules. Fifty different rules are more complex to administer than one set of rules. Such extreme decentralisation with 50 state election commissions running an election for the US president is bound to be more inefficient than one centralised election commission with a uniform set of rules for all.

The US’s intensely federal structure and its inevitable inefficiencies are a deliberate design and not an accident. A heavily decentralised model with powers handed down to state and local governments has served the US extraordinarily well. When states frame their own rules for governance and compete with each other, the larger nation benefits. For example, in the current election, one state — Maine — decided that the current electoral system of plurality voting is obsolete and chose the rank choice voting system for all elections held in their state. If it works well, it is likely that the other states may adopt it too.

Had there been one set of standard national electoral rules for all states, such a natural experiment would not be possible. Decentralisation enables a competitive marketplace among states and local governments that foster new ideas and innovation. Further, when the spectre of institutional capture looms large across many democracies currently, capturing one central institution is much easier than the ability to capture many institutions at the state level.

The staunch decentralisation and devolution of powers in the country’s system is perhaps a critical factor in the US’s overall success as a nation, that is much under-appreciated and recognised. Inefficiency is a small price to pay for much larger and more sustainable benefits.

In contrast, India is heavily centralised with a trend towards greater centralisation in recent years. The Goods and Services Tax (GST) regime, supported by both national parties, is one glaring recent example of how we as a nation sacrificed federalism at the altar of economic efficiency. Let us imagine a situation where the American company, Apple, wants to make a big investment in India. It is better for various states such as Tamil Nadu, Maharashtra, Karnataka, Uttar Pradesh to compete with each other to attract Apple to their state than for a prime minister or a Union Cabinet minister to decide where Apple should invest.

States can compete only when they have powers to frame their own rules over taxation, land, labour, environment and other areas. India’s states have been slowly stripped of most of their powers, including the basic right of taxation, which is the exact opposite of the US’s federal structure.

Some argue that it is wrong to compare India’s federal structure with the US’s where each state has sovereign rights with its own constitution, flag and boundary. It is a valid argument but has surpassed its validity period. India’s Constitution-drafters were right at that time to be apprehensive of secessionist tendencies of different states given India’s extreme diversity and hence adopted the approach of a strong Centre with limited powers to states.

Seven decades later, the time has come for India to devolve most powers to states and enable a more vibrant and competitive federalism environment, not centralise even more in the garb of “one nation one policy” and efficiency.

The fleeting chaos over the presidential elections will pass and the US will soon have a new President. But the underlying federal structure that has served the country admirably will remain steadfast, regardless of this chaotic experience.

Indian commentators may well be justified to want to export our election process to the US. It is of greater importance that India imports ideas of genuine devolution and decentralisation from the US.