Praveen Chakravarty

October 22, 2017

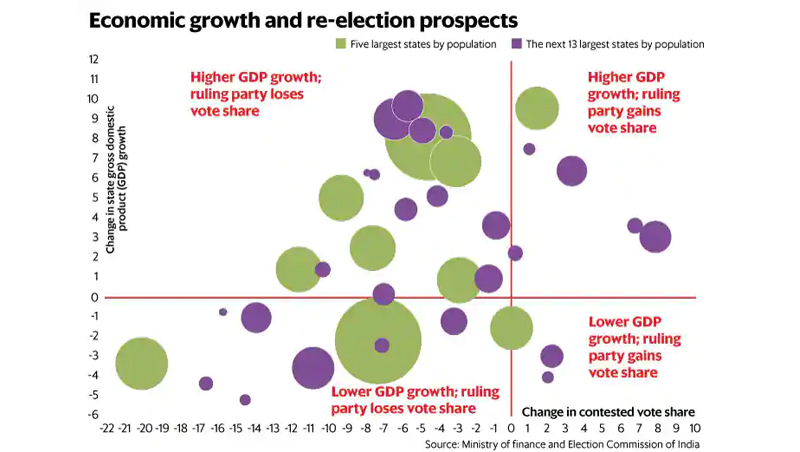

Apparently, “there is something in the New Delhi air”. Veteran political observers of India reckon that slowing economic growth over the last six quarters has infused pollutants into what was once considered the clean and visible air of the 2019 general elections. It is undeniable that measured in the metric of gross domestic product (GDP) growth, the economy has experienced a slowdown. Political science theorists and public commentators intuit a relationship between GDP and electoral outcomes and thus proclaim that the 2019 electoral air is now getting murkier. Successful re-elections in the last decade of Narendra Modi as chief minister of Gujarat, Nitish Kumar in Bihar and Shivraj Singh Chouhan in Madhya Pradesh are often cited as examples to argue that high GDP growth can help an incumbent get re-elected. In national elections, the National Democratic Alliance (NDA) government from 1999-2004 delivered average 5.8% GDP growth and was voted out while the United Progressive Alliance (UPA) 1 (2004-09) delivered 8% GDP growth and was voted back. The defeat of the UPA 2 in 2014 is cited as a counter example of losing an election due to a slowing economy when average GDP growth slipped to 7%. Thus, a slowing economy portends re-election dangers for the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) in the 2019 general election, goes the growing contention. Theoretical expectations of a strong relationship between GDP growth and electoral outcomes aside, does empirical evidence in India corroborate such a narrative? Do Indian voters reward or punish a ruling party for their performance on GDP growth? India’s electoral outcomes are notoriously complex and noisy to fit simplistic narratives around them. The most fundamental challenge for any electoral analysis in India is its unique nature of ever changing pre-election alliances across political parties, which renders comparisons across elections fallacious. India’s first-past-the-post electoral system complicates any analysis even further where political parties can win elections solely driven by smart alliances and identity politics than by exemplary governance. The Kumar re-election narrative is one such example. Contrary to popular belief, Kumar is no darling of the Biharis due to his perceived focus on economic development. As I have shown in my earlier writings, Kumar is not even the most popular leader in Bihar but he won successful re-elections primarily through opportunistic alliances with the BJP and then the Rashtriya Janata Dal (“Unravelling The Nitish Kumar Myth”, IndiaSpend, 28 July). Over the last decade-and-a-half, just as high-growth states such as Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh and Bihar re-elected their incumbents, other high growth states such as Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Karnataka and Rajasthan have always voted out their incumbents. Equally, low-growth states such as Odisha and West Bengal re-elected their incumbents while others such as Uttar Pradesh and Punjab voted them out. The picture is decidedly mixed and confusing. To emphatically assert a strong relationship between GDP and re-election based on a cursory analysis of electoral wins and losses is plain naïve.We adopt a revealed preference analysis of voter choices to test for the impact of GDP growth on voter preferences. We analysed nearly 700 million voter choices expressed across 36 state elections in the 18 largest states between 2004 and 2016 (two elections for each state). To minimize the effects of extraneous variables and purely measure voter preferences, we use contested vote share (the percentage of voters choosing a party in each constituency when given that choice) as a metric. This is not perfect but better than a simplistic headline win-loss analysis. We test change in contested vote share for the ruling party against change in state GDP (precisely, net state domestic product) growth rates during its tenure vis-à-vis the previous. Recall that a higher vote share across the state does not necessarily mean an electoral win. Put simply, we test if a ruling party gains vote share when it delivers higher GDP growth in its tenure than the previous tenure and if it loses vote share when it fails to deliver higher growth.In 27 of the 36 elections in this analysis, the ruling party lost vote share, regardless of GDP performance. But the ruling party won its re-election 19 times out of these 36—12 of them with a lower vote share. This establishes the fact that it is misleading to attribute a ruling party’s successful re-election directly to voters’ enchantment for its governance record. There is generally an anti-incumbency factor that results in a lower vote share for the ruling party which does not seem to be compensated for by delivering higher GDP growth. Further, there is no evidence that higher GDP growth leads to increased vote share for the ruling party. Of the 24 times that a ruling party delivered higher GDP growth than in the previous tenure, it still lost vote share in 18.But it is also misleading to assume each state is an equal data point where Uttar Pradesh with 80 million voters is treated on a par with Delhi with eight million voters. Since we are trying to answer the question if the average Indian voter’s behaviour is affected by GDP, it is important to weight each state by its voter population. Each dot in the chart represents one state election weighted by size, with the five largest states identified in a different colour. If the theoretical relationship were to hold true, we would have observed a clustering of these dots in the top right quadrant for a positive relationship between GDP growth and vote share. Instead, we observe a clustering in the top left quadrant. This indicates that, in general, most states are growing faster than before but that does not necessarily translate into a higher vote share for the ruling party. It can also be inferred that 75% of the time, the average Indian voter is not terribly enthused by robust headline GDP growth numbers and does not reward the ruling party with her vote. But does she punish the ruling party for lower GDP growth?

India’s electoral outcomes are notoriously complex and noisy to fit simplistic narratives around them. The most fundamental challenge for any electoral analysis in India is its unique nature of ever changing pre-election alliances across political parties, which renders comparisons across elections fallacious. India’s first-past-the-post electoral system complicates any analysis even further where political parties can win elections solely driven by smart alliances and identity politics than by exemplary governance. The Kumar re-election narrative is one such example. Contrary to popular belief, Kumar is no darling of the Biharis due to his perceived focus on economic development. As I have shown in my earlier writings, Kumar is not even the most popular leader in Bihar but he won successful re-elections primarily through opportunistic alliances with the BJP and then the Rashtriya Janata Dal (“Unravelling The Nitish Kumar Myth”, IndiaSpend, 28 July). Over the last decade-and-a-half, just as high-growth states such as Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh and Bihar re-elected their incumbents, other high growth states such as Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Karnataka and Rajasthan have always voted out their incumbents. Equally, low-growth states such as Odisha and West Bengal re-elected their incumbents while others such as Uttar Pradesh and Punjab voted them out. The picture is decidedly mixed and confusing. To emphatically assert a strong relationship between GDP and re-election based on a cursory analysis of electoral wins and losses is plain naïve.We adopt a revealed preference analysis of voter choices to test for the impact of GDP growth on voter preferences. We analysed nearly 700 million voter choices expressed across 36 state elections in the 18 largest states between 2004 and 2016 (two elections for each state). To minimize the effects of extraneous variables and purely measure voter preferences, we use contested vote share (the percentage of voters choosing a party in each constituency when given that choice) as a metric. This is not perfect but better than a simplistic headline win-loss analysis. We test change in contested vote share for the ruling party against change in state GDP (precisely, net state domestic product) growth rates during its tenure vis-à-vis the previous. Recall that a higher vote share across the state does not necessarily mean an electoral win. Put simply, we test if a ruling party gains vote share when it delivers higher GDP growth in its tenure than the previous tenure and if it loses vote share when it fails to deliver higher growth.In 27 of the 36 elections in this analysis, the ruling party lost vote share, regardless of GDP performance. But the ruling party won its re-election 19 times out of these 36—12 of them with a lower vote share. This establishes the fact that it is misleading to attribute a ruling party’s successful re-election directly to voters’ enchantment for its governance record. There is generally an anti-incumbency factor that results in a lower vote share for the ruling party which does not seem to be compensated for by delivering higher GDP growth. Further, there is no evidence that higher GDP growth leads to increased vote share for the ruling party. Of the 24 times that a ruling party delivered higher GDP growth than in the previous tenure, it still lost vote share in 18.But it is also misleading to assume each state is an equal data point where Uttar Pradesh with 80 million voters is treated on a par with Delhi with eight million voters. Since we are trying to answer the question if the average Indian voter’s behaviour is affected by GDP, it is important to weight each state by its voter population. Each dot in the chart represents one state election weighted by size, with the five largest states identified in a different colour. If the theoretical relationship were to hold true, we would have observed a clustering of these dots in the top right quadrant for a positive relationship between GDP growth and vote share. Instead, we observe a clustering in the top left quadrant. This indicates that, in general, most states are growing faster than before but that does not necessarily translate into a higher vote share for the ruling party. It can also be inferred that 75% of the time, the average Indian voter is not terribly enthused by robust headline GDP growth numbers and does not reward the ruling party with her vote. But does she punish the ruling party for lower GDP growth?

This analysis also reveals that there is more than a 90% chance that the average Indian voter punishes the ruling party for lower GDP. To be sure, the probability of the ruling party losing vote share in a re-election is high, regardless of GDP growth. In other words, the ruling party has a 75% chance that it will lose vote share when it delivers higher GDP growth but more than a 90% chance that it will lose vote share when the economy slows. So, higher GDP growth is not a sufficient condition for increased vote share but perhaps a necessary one. On the other hand, a slowing economy almost always results in a loss of vote share for the ruling party. Recall, this does not necessarily mean that the ruling party will not get re-elected. The relationship between slower economic growth and loss in vote share is marginally stronger than one between higher economic growth and gain in vote share. But overall, the relationship between economic growth and voter behaviour is at best, tenuous. Perhaps one can draw from the work of Nobel laureate behavioural economist Daniel Kahneman on negative biases and loss aversion to explain why Indian voters seem to punish ruling parties for a slowing economy more than rewarding them proportionately for rapid growth.

There can be various interpretations of this analysis but a simplistic explanation of GDP and electoral outcomes cannot be one of them. This analysis tests state GDP against state elections. Some may argue that it may be different for national elections. Again, there is no strong empirical evidence to prove that and my past research has shown that India’s national elections are just a series of state elections held simultaneously due to strong local currents. One could also argue that agricultural GDP growth, rather than overall GDP growth, could be more tightly linked to voter behaviour since more than half of India’s workforce is employed in agriculture. In our prior research, we have tested for a relationship between agricultural GDP growth and voter behaviour and found no strong relationship between the two. To account for “recency bias”, we have also tested for just election year GDP numbers rather than the average for the entire tenure and still found no strong relationship to voter choices. Another hypothesis could be that perhaps more than economic growth measured in GDP terms, inflation could be a better macroeconomic variable to predict voter behaviour. Again, our prior research finds no evidence of a relationship between short-term and long-term inflation effects on voter choices. All this research is available on IDFC Institute website. Admittedly, this is a simplistic analysis that does not involve building a complex regression model to predict voter behaviour, as some modern-day scholars would prefer. Indeed, it would be audacious to believe that one can build a mathematical model to predict the behaviour of the Indian voter.

Notions that voters reward good governance and economic growth are too simple and idealistic for the staggeringly complex electoral democracy that India is. It is unclear that economic variables play a decisive role in shaping the average Indian voter’s behaviour as much as the educated elite would like to believe. The temptation to capsule down complex electoral outcomes to misleading, evidence-free, simplistic narratives consumes the political commentariat class. One cannot make grandiose proclamations about GDP growth and re-election chances of a ruling party. At best, it can be said that there is a slightly higher likelihood of a drop in vote share for the ruling party when the economy slows down. This perhaps explains the nonchalance of that astute politician, BJP president Amit Shah, to the current English media cacophony over a slowing economy.

With inputs from Swapnil Bhandari.

Praveen Chakravarty is a senior scholar at IDFC Institute, a Mumbai-based think tank. Comments are welcome at theirview@livemint.com