The conventional wisdom is that the people of TN are yearning for a change from the Dravidian parties.

Praveen Chakravarty

December 29, 2014

A detailed analysis of nearly 25 years of electoral data, in each of Tamil Nadu’s 234 assembly constituencies in the last 10 elections (Lok Sabha and assembly) since 1991, provides some interesting insights.

A palpable sense of curiosity has gripped Tamil Nadu’s political observers. Former Union shipping minister G.K. Vasan, among the few to emerge unscathed from the alleged scams of the UPA regime, recently broke away from the Congress and amid much fanfare, launched his own political outfit, a reincarnation of the Tamil Maanila Congress started by his late father G.K. Moopanar.

Vasan insinuated that the Congress party’s command and control culture is ill-suited to Tamil Nadu’s rapidly changing political landscape. Political commentators, newspaper editors and others hailed this move by Vasan as a potential harbinger of liberation from the clutches of the Dravidian parties that have ruled the state since 1967. There have been editorials urging Vasan to usher in a new, non-Dravidian style political culture in Tamil Nadu. The conventional wisdom is that the people of Tamil Nadu are yearning for a change from the Dravidian parties.

How real is this narrative about voters’ desire for a non-Dravidian politics? A detailed analysis of nearly 25 years of electoral data, in each of Tamil Nadu’s 234 assembly constituencies in the last 10 elections (Lok Sabha and assembly) since 1991, provides some interesting insights.

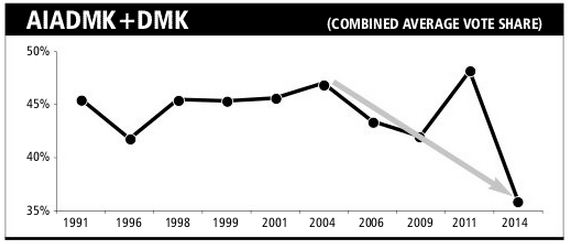

The average combined contested vote share of the AIADMK and DMK held steady from 1991 to 2004, and started to decline steadily since the 2004 election, to hit an all-time low in the 2014 Lok Sabha election. From a 45 per cent average combined contested vote share in 1991 to the peak of 47 per cent in 2004 for the two major Dravidian parties, it slid to 42 per cent in 2009 and to 35 per cent in 2014. This drop of 10 percentage points in vote share would be enough to swing any election, if all of it were captured by one entity.

While alliance arithmetic has often played the swing factor in Tamil Nadu elections since 1991, the analysis of electoral data reveals that since 2004, 6-10 per cent of voters have been in constant search for a non-Dravidian alternative. Since constituencies were redrawn after the delimitation exercise by the Election Commission, voters in Tamil Nadu have had a chance to exercise their franchise in three major elections — 2009, 2011 and 2014.

There were 54 common constituencies where both the AIADMK and DMK contested in all three elections — 81.5 per cent voted for either of the two parties in 2009, 77.5 per cent in 2011, and only 71.7 per cent in 2014. In the same constituencies, there is a consistent decline in the combined vote share of the two parties. Similarly, there were 80 constituencies that had both an AIADMK and a DMK candidate on the ballot in the 2011 and 2014 elections. The combined force lost vote share in 78 out of these 80. In a vast majority of constituencies, voters increasingly voted for a third option, other than the two major Dravidian parties.

What is more striking is the devil in the detail of the AIADMK’s supposed landslide in the 2014 election. There were 165 assembly constituencies with an AIADMK candidate in both the 2011 assembly and 2014 Lok Sabha elections. The AIADMK lost vote share in 148 of these in 2014. That the party still managed to win 37 of the state’s 39 seats in the 2014 parliamentary election, despite a 9 per cent drop in vote share from 2011, is a manifestation of India’s first-past-the-post electoral system. In fact, all Dravidian outfits, including the MDMK and DMDK, lost significant vote share in the 2014 election vis-à-vis the 2011 election.

Further, in the 2014 Lok Sabha polls, wherever the AIADMK was pitted against another Dravidian spinoff, such as the DMDK or MDMK, it did much better than when pitted against a non-Dravidian outfit like the BJP or a communist party. This implied that, given a choice of only Dravidian outfits, voters preferred one of the two major parties. It is abundantly evident from this analysis that despite the winner-takes-all electoral tradition of Tamil Nadu’s politics — where the DMK and AIADMK have taken turns at winning a large majority and capturing power for the last 25 years — the vote share for both parties together has been steadily declining since 2004.

That there is a simmering longing for a non-Dravidian political outfit among voters in Tamil Nadu is indisputable from electoral data analysis. A consensus political alternative or even a leader who can harvest this brewing desire for change and win power is yet to emerge. Vasan could not have timed his move better, coming at a time when the combined vote share of the two major Dravidian parties is at an all-time low, with an election looming. Can he meet such lofty expectations and be the one to unseat the Dravidian parties in 2016, after nearly 50 years?

https://indianexpress.com/article/opinion/columns/looking-for-a-non-dravidian-answer/