Praveen Chakravarty

March 18, 2019

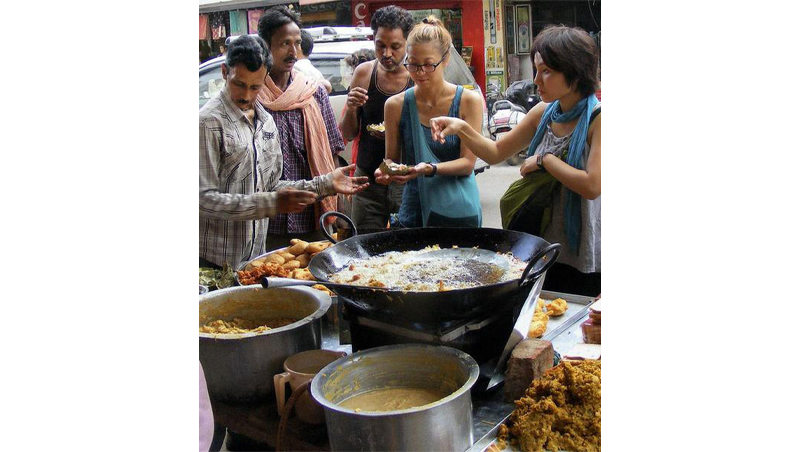

Varanasi: Two foreign tourists buying ‘pakodas’ (an Indian snack) from a roadside vendor in Varanasi on Thursday. PTI Photo (PTI7_5_2012_000038A)

There is obfuscation over both the existence of a jobs crisis and the diagnosis of it

It is well established that India is staring at a massive jobs crisis. Every single survey points to jobs as the biggest issue concerning voters, especially the youth. Yet, the Prime Minister and the government steadfastly refuse to even acknowledge this issue, let alone address it.

India’s jobs crisis is an economic issue, not a political one. India is not unique in experiencing rising joblessness and, consequently, income inequality. Many developed and developing nations are grappling with this problem, too. Such a crisis requires acknowledgement of the issue first, then a vibrant public debate on solutions to tackle the crisis, and finally, a coordinated implementation of ideas. Instead, there is much obfuscation over both the existence of a jobs crisis and the diagnosis of it.

Demand and supply

The latest in this obfuscation is the notion that India does not have a jobs crisis but a wages crisis. According to this argument, every Indian youth who wants a job can get one, but not the wages she wants. This is a banal argument. This is akin to arguing that every Indian who wants to buy a house can buy one but just not at the price she can afford. What determines the price of a house? Apart from external factors such as taxes, the price of a house is simply determined by the demand for houses versus the supply of houses. Similarly, what determines wages for an employee is the demand for such skills versus the supply of such skills. Wages are not determined by some external factor that is removed from labour market conditions. It is entirely a function of the labour market. In economic parlance, wage, or the price of labour, is an endogenous variable and not an exogenous one.

Let us understand this through the Prime Minister’s favourite example of frying pakodas, which is apparently an evidence of the plentiful jobs that we are creating. The wages for a person frying pakodas is determined by the demand for pakodas in the economy and the supply of pakoda fryers. If the wages for pakoda frying are very low, it can only mean that there are far more people willing to fry pakodas for a job than there is demand for pakodas. Hence, their wages continue to be low. In other words, the economy is not creating enough opportunities for the large number of unemployed people other than to fry pakodas at minimum wages. Of course, a person frying pakodas in a five-star hotel will get paid higher than a roadside pakoda fryer, presumably because her skill and productivity level are different. But for that same skill level, the wages of a person are determined largely by the demand for such skills and the supply of people with such skills. If demand is higher than supply, wages automatically rise; if not, they remain stagnant. To understand the unemployment issue as a wages problem shows ignorance.

Even if we grant the outlandish assertion that India has a jobs bounty but wages are not rising, this points to a labour market failure. Are we then saying that workers need to get unionised more and demand higher wages since the price of labour is not commensurate? It is a facile argument.

The proponents of the argument that there is a wage crisis and not a jobs crisis would do well to go back to economic history and study the work of Arthur Lewis, the Nobel Prize-winning economist from the West Indies. Lewis, in his seminal work in 1954, showed how in economies such as India and China, which have an “infinite supply of labour”, there tends to be a two-sector economy — the capitalist sector and the subsistence sector. His summary finding was that the living standards of all citizens in such two-sector economies are determined by the wages of the people in the subsistence sector. If there is demand for labour and skills in the capitalist sector, then the endless supply of labour from the subsistence sector will transition, and wages will ultimately rise only when the demand for labour exceeds the supply of labour in the subsistence sector.

The harsh and simple reality of India’s jobs situation is that we are not creating as many jobs as we need to. There can be many reasons for the lack of our ability to generate enough jobs but at the very least, we must first acknowledge this problem. Calling this a wages crisis and not a jobs crisis is neither helpful nor sensible. It is very critical that we don’t bury our heads in the sand and pretend that there is no jobs crisis but only some wage crisis, induced by labour market distortions. There could well be labour market failures too, but it is not a sufficient explanation for the jobs crisis.

Formalising the economy

The proponents of the ‘there is a wage crisis’ argument also go on to say that the largely informal nature of India’s economy leads to low productivity and hence keeps wages low. So, their solution for higher wages is to embark on a mission to explicitly formalise India’s economy. Again, economic history tells us that formalisation is an outcome of economic development, not a cause. No large market economy in history has embarked on an explicit economic policy for forced formalisation. The U.S. had its large share of ‘petty retail traders’ before World War II, which then paved the way for large-scale organised retail with advancements in transport infrastructure, technology and rising income levels. The U.S.’s economic policymakers did not wake up one morning and say, “The informal mom-and-pop retail industry is bad, so let’s formalise it by ‘demonetising’ the entire economy.”

India’s economic commentary today carries a ‘blind men and an elephant’ risk. It has a tendency to claim absolute truth based on limited subject experience. There is no need to complicate the state of India’s jobs market. The simple truth of it is that we do not produce enough jobs.

Praveen Chakravarty, a political economist, is chairperson of the data analytics department of the Congress party